By the time I reached seventh grade, and Hereford Jr.-Sr. High School, I had lost my swagger. I had always been the guy who made the girls laugh, but now I was just another fish in a big pond, and it took me a while to figure things out. It was customary adolescent uncertainty, but there was more.

Junior high was my introduction to social strata. In my last few years in Timonium, when I looked around, I saw equals. My classmates and I were from the same community, and we thought the same way. Junior high was my first taste of diversity. Not in the modern sense (Hereford was mostly white and everyone spoke English), but in the true sense. Kids from far-flung areas and backgrounds, who settled into various cliques. And I would never again be counted among the hip.

I was fine with that. My mature self would be a fierce individualist and non-conformist, and it was never that important to me to be popular. Or be seen as belonging to any group. I’m an introvert. There is a silly notion current that you have to either lead, follow, or get out of the way. There’s a fourth option. The lone wolf. The guy who does his own thing (which goes against the popular thinking that the collective is everything).

To be cool requires compromise. You can’t be too cerebral; and you can’t be seen as too virtuous. I never saw any reason to present myself as less than I was, and thanks to my Christian upbringing (except for the fact that I was a general smartass), I was pretty virtuous.

As the years passed, I found my comfort zone with the smart guys. Jim, the two Bobs, and Joe were probably regarded as nerds, but they were my circle. I don’t think my classmates saw me as a nerd because I was an athlete, which, in and of itself, conferred a hefty number of coolness points. I never gave the matter much thought. Those guys were my friends.

It didn’t help that I was so clueless with girls. I was always infatuated with one girl. It would be her, or no one. Every few years the girl would change, but my shyness would abide. Perfectionist that I was, I thought you had to be James Bond smooth to get the upper echelon girls. It never dawned on me that even 007 started somewhere. Or that maybe you could just be yourself. It was funny that at the last class reunion I attended, I don’t recall talking with a single male the entire evening. I think being the quiet guy (who was also good in track) had lent me a certain air of mystery with the ladies. Go figure.

I was still a good student, and that would last for several more years. The seminal moment in my career came in the spring of 1966, when I discovered Track and Field News in the school library. I would play baseball again that summer, but it would be for the last time. I fell in love with track. I had always watched the meets on TV with my father, but never seen myself doing it. And I hadn’t exactly set the world on fire the previous fall when I finished 31st in the seventh-grade cross-country race; a source of endless hilarity for my friend Winston, who had finished second in the eighth-grade race.

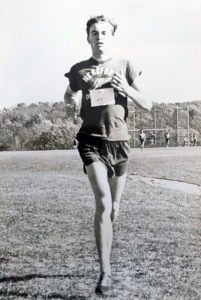

But that spring, maybe thanks to my new passion for the sport, I ran the fastest 880 (half-mile) of all the seventh-graders. All I remember about it was that I paced myself so I wouldn’t die at the end. I bought a pair of adidas, and started running on my own. The next year the coaches let me work out with the team even though I wasn’t eligible to compete. That spring, in the eighth-grade meet, I won the 880 by about 80 yards.

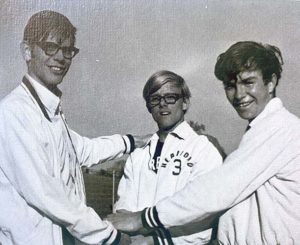

The next fall, Winston and I wanted to run cross-country, but Coach Heffner said there wasn’t enough interest to field a team. All the good guys from the previous year’s squad had graduated, or moved on to extra-curricular activities less demanding than running up and down hills all day. Coach was fair about it, though. He told us if we could scrape together seven guys, we could have a team. Fortunately, Winston and I had enough friends we could bully into joining us. Donald Harris, a fine sprinter from the track team, also signed on. I’m not sure what he was thinking, but we were glad to have him. The rest is history. We would go on to win two state championships while I was there, and many more in the years to come. Between myself, and three of my brothers, we would win six individual state championships. My brother, David (a real cross-country animal), would win three. Most years the state and county meets were held at Hereford, and David was the only high-school runner to ever break 15:00 for the mountainous three-mile course—doing it twice.

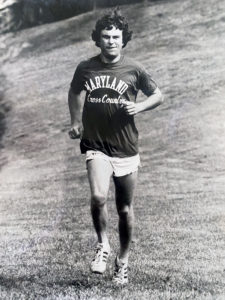

Thanks to the patience of coaches Heffner, Bowen, and Zablocky (I was a coach’s nightmare), I had a fairly successful high school career—which landed me at the University of Maryland, after also being recruited by Navy and Penn.

During this time, my obsession with sports continued, but now I was almost exclusively focused on track. I devoured every issue of Track and Field News. I knew all the runners and their times, and even the splits from their best races. (Funny story. When I met my wife in California in 2009, I told her about a runner from her own high school—a classmate she had never heard of!) In short, my mind was a treasure trove of useless information—unless I aspired to a career at ESPN, which hadn’t been invented yet. By the time I graduated from Hereford, I had pretty much checked out as a student.

Now, a word about my mother and father. I did not have, in the modern parlance, parents; I had a mother, and I had a father. My brothers and I were grounded in the difference between right and wrong. Though not a big man, my father was a pillar. He was the sole provider, which included working three jobs during lean times. My parents met when both worked for a popular Baltimore brewery; my father as an ad executive, my mother as the president’s secretary. When the brewery went under (I guess it wasn’t that popular) my father became a distributor for Pepsi-Cola in Northern Baltimore County. During winter months business slacked off, and he once worked part-time for the post office during the Christmas season delivering mail in his Pepsi truck. You can’t keep a good man down. When the local bottler did away with distributors, Dad became sales manager for Baltimore Pepsi. He would later go on to tremendous success as regional manager of sales for a national company out of West Virginia, marketing vending machines to Coke and Pepsi bottlers in the Northeast. After a year or two getting his bearings, he was the top producer in the nation for a number of years running. Dad didn’t finish college, but he was the smartest man I ever knew, with an uncanny knack for judging a man’s character. He was generous to a fault, and it was only upon his death in 1999 (and his viewing which was spread over two days because of the turnout) that I heard from all of the people that he had helped over the years. Dad was a thoroughly charming man, with a laugh that could fill the largest room. But what he loved best, were the quiet times with my mom. I don’t know if you can ask anything more from your father than that he adore your mother. And Dad did. His wife, and his family.

My mother was every inch his equal; she and my father perfectly suited to one another in spite of the eleven-year age gap. Mom was a brilliant student. She came from a working family in East Baltimore, and she received an academic scholarship to The College of Notre Dame of Maryland, where she earned her B.A. in English. She was, quite simply, the most learned person I’ve ever known. She was a walking encyclopedia. My daughter, twenty or so at the time, once had a question for me I couldn’t answer. “Call your granny and ask her,” I said. “I’ll do that,” she told me. “Granny knows everything!” Mom was, in her own words, a man’s woman. Unfailingly practical, she was a credit to my father in that she could stretch a dollar like no one I’ve ever seen; our comfortable life owing as much to Mom’s frugality, as to Dad’s generous provision. Her family was everything to her; her husband, her sons (all six of us), and her grandchildren. Mom was so cute; so proper. Men rushed to open the door for her. And she was so well-rounded in her knowledge that she could converse with anyone, on any level. My brothers and I could talk to her on the phone for hours. She was my writing coach, and biggest booster. She taught me everything I would ever need to know about the speaking of proper English. The only sadness in her life—that she only had my father for those forty-seven short years.

The University of Maryland in the fall of 1971 was another dose of culture shock. Hereford High was Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood by comparison. My second day in the dorm, I happened upon a guy and his girlfriend in the shower. At Hereford they made boys and girls shower separately. I found out what a homosexual was. This, testament not only to my naivete, but to the sorry fact that I had never progressed very far in my Bible or history studies. (“They do what?”) You could smoke in class. But most illuminating was my introduction to the counter-culture.

We were a couple of years removed from Woodstock, but the hangover was a beaut. It felt like they had just picked up the whole shebang, and moved it a couple hundred miles south. Lying around like a bum all day was not only beneficial for one’s mental health, it was socially responsible. You were gettin’ your shit together. In some ways, I fit right in! There was hair, and lots of it. At Maryland, you were a freak; or a straight. I learned that smoking grass expanded your mind. There was so much mind expansion going on, it was a good thing we had that big campus.

All that said, I was happy to be there. I loved being on my own. I had my head on pretty straight (except for the not going to class part), and found the whole scene pretty entertaining. Funniest of all were the earnest types; the ones who took all the bullshit seriously. (They would go on to chair Diversity Departments.) There were some issues to be dealt with, though, including, and especially, my first roommate in Calvert Hall. He of the natural cologne that was all the rage. Who also had a special fondness for my expensive stereo. “Far out,” he said, or words to that effect, the moment he laid glassy eyes on it. The guy had to go.

I was offered a room with Myron in Baltimore Hall, next door. Myron was a seven-foot high jumper. He had gotten his previous roommate, a pretty good shot putter, kicked off the team for smoking weed. In a dramatic about-face, by the end of that school-year Myron had become one of the premier dope dealers on campus. He had two drawers filled with ludes. He was a good roommate though. I don’t remember any gun battles, or anything like that.

I don’t know if you could have found a more colorful band of misfits than those populating the Maryland athletic program in the seventies. Guys from New York and New Jersey abounded, usually at the forefront of the merrymaking. Baltimore guys more than held their own. Philly guys came packing a sour attitude. I’ve always thought that Philly has a complex about playing the weak sister to New York; whereas Baltimore is content with who she is (we just hate Washington). Guys from the DC area were, by and large, pretty vanilla. No one from the South (or Massachusetts) ever came to Maryland. Whatever our origins, brothers in hooliganism shared a common bond. No one went to class.

(My freshman year experiences at Maryland were the basis for my second screenplay, Winged Foot.)

“The race is not always to the swift…”

Being on a team is like being in a fraternity. You get an instant bunch of friends. Especially distance runners, because you spend so many hours together, pounding out the miles. But even there, social strata come into play. It’s hard to say why some guys get singled out as targets. But once the poor victim had one on his back, it could be brutal. The proverbial needle more resembles a dagger. I was accepted, mostly because I was as quick with a one-liner as anybody. And I did dining hall impressions (we lived in the dining hall). It was almost like being back in fourth-grade! It’s the rare guy who can let the abuse roll off his back. Most can’t hack it. They quit the team, or transfer.

A final word on distance runners. At the end of the day, in spite of not darkening a single classroom, or cracking one of the textbooks on the desk nearby (probably buried under a mountain of running gear), or, for that matter, earning a dime through honest industry; if we could look back on a brisk five or six miles covered that morning, followed by a tough track workout that afternoon, we could pop a beverage, put up our feet, and pat ourselves on the back for a job well done.

My friends and I were the smartest people on campus, and our esteem was such that we were never burdened by any imperative to prove it in the classroom. We let our winged feet do the talking. We had some successes, with a couple of ACC titles in cross-country, and a win here and there against our hated rival, Navy. And in the glory days of Maryland basketball under Lefty Driesell—we were devoted followers. We never missed a game. Terps!

On paper, this might not sound like the ideal training ground for a successful novelist. But I did take two years of typing in high school; and did, in time, come to that moment of truth experienced sooner or later by all great writers. When, after thorough self-analysis, he comes to the conclusion that, yes, degreed or not, he is smarter than the rest.

**My debut novel, #ScaryWhiteFemales—a hilarious parody of the war on men—is on sale now!